Ernest Hemingway and Tony Oliva: A Tale of How They Met in Cuba

This (somewhat) fictional story is a tribute to two men whose love for Cuba and baseball is beyond question: Ernest Hemingway and Tony Oliva. In the summer of 1960, Hemingway was sixty years old and in failing health. He and his fourth wife, Mary, were forced to leave their bucolic estate southeast of Havana. For nearly twenty-two years, the Hemingways had made the Finca Vigía (i.e., ”Lookout Farm”) their home base, but now, under pressure from the U.S. government to leave Cuba, which was becoming more dangerous under the new Communist regime, they vacated their beautiful, fourteen-acre property just outside the little village of San Francisco de Paula. Meanwhile, Oliva was playing baseball for his country team in the Pinar del Río province in western Cuba. This story is part yarn, part fantasy and part truth. It is left to the reader to decide which parts are true and which are fiction.

Episodes

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

Mary Hemingway met Maria and Manolin, Pedro Jr.'s cousin, at the Finca not long after Hemingway committed suicide on July 2, 1961.

Manolin said, “Mrs. Hemingway, I want to show you something.”

He was holding a small package, postmarked Rochester, Minnesota, dated June 1961. Manolin opened it to the dedication page of The Old Man and the Sea, the book where Hemingway had paid tribute to his publisher, Charles Scribner, and editor, Max Perkins.

Under the dedication, Hemingway had written, in his distinguishable handwriting:

“To Manolin. You helped two old fishermen—Santiago and me—attain humility. I am sick now, and I have a hard time remembering things. Without memory, a writer is out of business, like a fisherman without bait. But please don’t worry. As you will read in this book, man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed but not defeated. I wish you the very best.

Ernest M. Hemingway, June 16, 1961.

P.S. I see from the papers that your cousin Pedro is tearing up the Appalachian League—he’s hitting over .400. My, what a pretty swing!”

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

Pedro Jr. signed with the Minnesota Twins in February 1961. The U.S. invaded Cuba in April 1961, landing at the Bay of Pigs. Papa Hemingway died of self-inflicted gunshot wounds in Ketchum, Idaho on July 2, 1961.

Papa Joe Cambria remained as a Twins scout when the Washington Senators moved to Minnesota in 1961. By then, he had signed over four hundred Cuban ballplayers to contracts with professional baseball teams in the United States. Early in 1962, he became very sick. Papa Joe Cambria was flown from Havana to Minneapolis to be treated at the St. Barnabas Hospital in Minneapolis. He died on September 24, 1962.

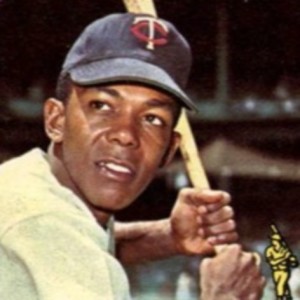

Pedro Jr.—aka “Tony” Oliva—led professional baseball with a .410 batting average with the Minnesota Twins Appalachian League affiliate in Wytheville, Virginia in 1961. Tony Oliva who officially became a U.S. citizen in 1971 on the heels of his third American League batting crown.

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

The phone crackled. The voice at the other end of the line was soft, almost muffled. Papa Hemingway was at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where he was being treated for hypertension and depression. At least that’s what the doctors said. The electromagnetic shock treatments weren’t helping much. He was still depressed, and damn, he could hardly write a few sentences without breaking into tears. He was not only losing his memory—he was beginning to lose his mind. But he remembered Papa Joe and his promise to help.

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

Heads turned as Papa Joe and Papa Hemingway entered Gran Stadium, making their way to the box seats behind the third base dugout. Pedro Jr. was second in line to take pre-game batting swings. When it was his turn, he dug in deep with his right foot, as close as he could get to home plate. This closed stance, as they called it, gave him a better bead on the ball as it left the pitcher’s hand. Even back then, Pedro believed with all his heart that he was a better hitter than the pitcher was a pitcher.

Serve it up, big guy. He liked them all. Fastballs, curveballs, changeups, even spitters. Didn’t even matter if the pitch was in the strike zone.

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

After Batista and Castro, Papa Hemingway was the most recognizable person in Cuba. Papa was in a good mood today. He had emptied his flask when Juan, his driver, escorted him to the bar in his 1955 red Chrysler convertible. Now, at the Floridita, he was into his second drink. The doctor had said no more alcohol but, hell, he thought, his body needed booze as much as a racecar needed oil.

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

In 1951, Papa returned to the story idea hatched in 1936 about the old fisherman. The original idea had but one character. Now, however, Papa imagined a story with two characters: the old man, of course, but also the boy. He recalled the special friendship between Manolin and the old man. Even after the old man lost the big fish, he continued fishing until he could no longer bait the hook. Until then, each day, the boy would run into the La Terraza restaurant, saying, “Please, sir, one cold beer, two sardines and the newspaper for the old man. He is thirsty and hungry and he comes again, today, with no fish. How are the Yankees doing? DiMaggio?”

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

One of the seven people Papa and Marty hired to run the Finca was twenty-six year-old Maria Petrona Lopez, from the fishing village of Cojímar. Papa knew the village well, as he docked the Pilar in its little harbor. Each morning, except Sunday, Maria would take the twelve-mile bus ride from her family’s little house near La Terraza Restaurant, to the front gates of the farm. Though it was only twelve miles, the rickety, stop-and go-journey often took more than an hour each way. Passengers got on and off the bus with heavy loads of fruits, vegetables, and chickens. Goats, and even pigs, were sometimes tethered to steel rails on the roof.

Maria had five children. One was named Manolin.

Thursday May 05, 2022

Thursday May 05, 2022

The year 1940 was monumental for Ernest Hemingway. His book, For Whom the Bell Tolls, was published; he married Martha, and together they moved to Cuba and the Finca Vigía, about ten miles southeast of Havana.

Pedro Oliva, Sr. often escorted gringos like Papa Hemingway on quail shoots on his little farm outside Entronque de Herradura, roughly twenty-five miles east of the provincial capital, Pinar del Río. The hunting in the area was excellent. Of the ten children raised by Pedro and his wife, Anita, there were five girls and five boys. The third child, the first boy, loved baseball from the moment he could hold a bat. His name was Pedro Jr., and he was born in July 1938. The next boy, Antonio, came along almost three years later.

Wednesday May 04, 2022

Wednesday May 04, 2022

Cast of Characters

Anita Oliva –Wife of Pedro Oliva, Sr.; her oldest son is Pedro Oliva, Jr.; she is also Maria’s youngest sister

Antonio Oliva – Younger brother Pedro Oliva, Jr., by three years

Calvin Griffith – Majority owner of the Washington Senators

Gigi Hemingway – Nickname for Papa’s nine-year-old son; his real first name is Gregory (Gigi is pronounced with a soft “g”, as in “the rock band had a ‘gig’ to play”)

Manolin – A boy who lives in Cojímar; his best friend is an old fisherman; his younger cousin, from Pinar del Río, is Pedro Oliva, Jr.

Maria Petrona Lopez – Manolin’s mother; she commutes each day, except Sunday, to work as a housekeeper at the Finca Vigía; her younger sister is Anita Oliva (Maria, therefore, is Pedro Oliva, Jr.’s aunt

Martha Gellhorn –Papa’s third wife; her nickname is Marty

Mouse Hemingway - the nickname for Papa’s second oldest son; his real first name is Patrick

Papa Hemingway – Ernest Hemingway, the famous author

Papa Joe Cambria– A well-known scout for the Washington Senators in the 1940s and 50s

Pedro Oliva, Jr. – Born on July 20, 1938, he is about 2 ½ years old when he first meets Papa Hemingway at his family’s farm in the province of Pinar Del Río, 100 miles west of Havana; his older cousin, Manolin, and his aunt, Maria, now live in Cojímar. In the United States, Pedro Jr. would go by the name of his next youngest brother, Antonio, or “Tony” for short

Pedro Oliva, Sr. - Anita’s husband and father of 10, including Pedro Jr. and Antonio

Santiago, the Old Man – Lives in shack, near the wharf, in Cojímar; his best friend is the boy, Manolin

Wednesday May 04, 2022

Wednesday May 04, 2022

Ernest Hemingway loved to tell stories. Hemingway biographer Carlos Baker called these stories “yarns.” His good friend, Aaron Hotchner, called them “practical joke fantasies.” Like all good storytellers, Hemingway exaggerated. Often, though, such talk gave him inspiration, and sometimes found its way into his writing.

Tony Oliva tells a few good stories, too, but his greatest story wasn’t a joking matter, nor one that he has shared, to this day, with anyone but his closest family members. The most plausible story is the one recounted by Oliva’s biographer, Thom Henninger. In Tony Oliva: The Life and Times of a Minnesota Twins Legend (2015). In order for likeable young Oliva to have a realistic chance of being signed to a long-term contract by the Twins, he needed legal documentation showing an age approaching twenty. The Minnesota Twins weren’t interested in older prospects—if a prospect were over twenty, the Twins would likely pass. Oliva, though, was actually approaching his twenty-third birthday, an age that would most likely be out of the ballpark for Twins owner Calvin Griffith. Papa Joe Cambria believed in Oliva, though. The young man could hit almost any pitch in and out of the strike zone, and he could drive the ball to every nook and cranny in the stadium. If the Twins saw what he saw, Cambria knew that Oliva was major league material.

Ernest Hemingway and Tony Oliva

Ernest Hemingway loved to tell stories. Hemingway biographer Carlos Baker called these stories “yarns.” His good friend, Aaron Hotchner, called them “practical joke fantasies.” Like all good storytellers, Hemingway exaggerated. Often, though, such talk gave him inspiration, and sometimes found its way into his writing.

Tony Oliva tells a few good stories, too, but his greatest story wasn’t a joking matter, nor one that he has shared, to this day, with anyone but his closest family members. The most plausible story is the one recounted by Oliva’s biographer, Thom Henninger. in Tony Oliva: The Life and Times of a Minnesota Twins Legend (2015). In order for likeable young Oliva to have a realistic chance of being signed to a long-term contract by the Twins, he needed legal documentation showing an age approaching twenty. The Minnesota Twins weren’t interested in older prospects—if a prospect were over twenty, the Twins would likely pass. Oliva, though, was actually approaching his twenty-third birthday, an age that would most likely be out of the ballpark for Twins owner Calvin Griffith. Papa Joe Cambria, a scout for the Twins, believed in Oliva, though. The young man could hit almost any pitch in and out of the strike zone, and he could drive the ball to every nook and cranny in the stadium. If the Twins saw what he saw, Cambria knew that Oliva was major league material.

How did Cambria make the Twins believe that Oliva was three years younger? No one really knows except for Tony and his family, but one thing is for certain: he needed help. Such aid, I suggest in this story, could have come from another Cuban Papa: they called him Papa Hemingway.

Soon, the entire story will be available as an e-book on Amazon. If you want to learn a bit more about me--a lifetime fan of the Minnesota Twins and of Hemingway's stories--then visit http://curtdeberg.com.